The sensilla are the receptors located on the beetles’ antennae.

All perceptions and orientations flow through them.

Artist Devi Petti studies entomology and creates the Insectomania series – earrings, rings, necklaces, pins – to let our bodies interact with a place in nature we often traverse with disinterest, superficiality, if not repulsion: the insects’ world.

With Sensilli, we interact with the unknown, the hidden, the unpredictable:

a new sensitivity opens up new realities.

In the latest series’ experiment Sensilli, the artist moulds four silver tea-spoons, handmade with the lost-wax technique, and inspired by the texts that her entomologist friend Sibilla − invented as all real characters are − wrote during her journeys in search of rare beetles.

Kamčatka, Hà Giang, Queensland, Newfoundland… With Sensilli we search for a vibration in tune with our dormant senses, similar to the crackling of silver being moulded, to the quiet ticking of the last monsoon rain.

Project made for Lake Como Design Festival

exhibited in the contemporary design selection curated by Giovanna Massonii

Rub’ al Khali, the Empty Quarter

For something to be interesting, you just have to look at it long enough, wrote Flaubert.

What is a teaspoon for you? Observe the autonomous movement of your hand as you mix sugar with coffee. You need no real concentration to perform the gesture. And in fact your thoughts, as the teaspoon is spinning, dissolve in the water too.

Where did that teaspoon come from? Was it always yours? Was it a gift?

I always go back to the same image. Sibilla, in the living room of her red house in Tangier. She gets the silver spoon from the velvet case, and with exact calm mixes the sugar with the green tea.

I watch her hand moving, then and now: closing my eyes is enough to see Sibilla’s strong tendons, precise as a chisel; her hand moving the teaspoon through the air, emphasising the significant elements of the stories her voice unfolded around us. She recounted journeys.

Kamčatka, Hà Giang, Queensland, Newfoundland… Is it possible to see everything, in one lifetime? Sibilla got very close to the Everywhere.

When she left, I crossed the sea and visited her home for one last time. I looked everywhere for the spoon. There was no trace of it, as if it had vanished along with her and everything she had told me, while clutching the silver teaspoon handle. Instead I found, in the dressing table, a series of notebooks bound in black leather: drawings of beetles and hints of conversations.

In the least worn notebook, perhaps the most recent, Sibilla tells of the Empty Quarter, the desert south of the Arabian Peninsula. She had confided to me verbally − I remember it very well – that in the desert she speculated, in the secrecy of her imagination, to which ‘poles of inaccessibility’ her mind might wander. She was attracted to the anarchy of the desert, not only because every rule could be considered suspended there, but also because, in the absence of rules and judgements, the very idea of the Self loses importance. In short: absolute freedom.

In the notebooks the story is expanded, and the purpose of the journey becomes an encounter.

The silence of the Empty Quarter facilitated the search. The beetles, down here, I found through hearing. It is a place where sounds, distinct from the nothingness in which they deflagrate, are not only heard: they go beyond the eardrum and, passing through unknown tunnels, settle at the bottom of the mouth. I listened to them and tasted them. It was like eating sand, of course. And the sounds from which they originated − the slap of wind on the desert, the slithering snake, the swaying of a dune − spread overwhelmingly in my mouth, every second more intense, every minute more bitter. I took out my teaspoon and used it to placate them: I pressed my tongue against it, and the silver particles that spread in my mouth allowed me to reactivate the sense that guides me in my search.

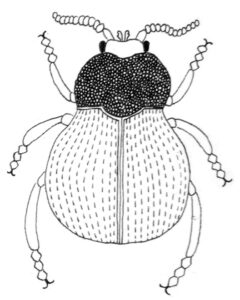

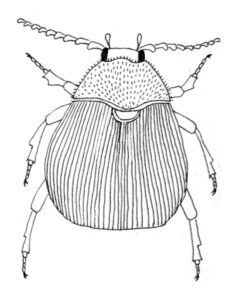

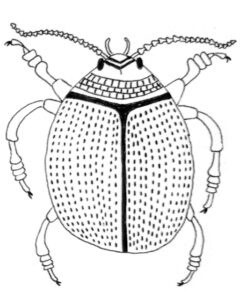

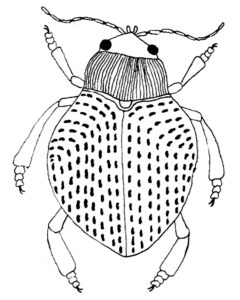

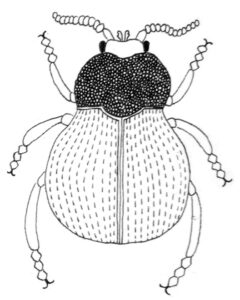

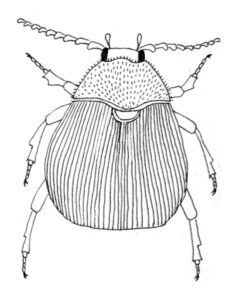

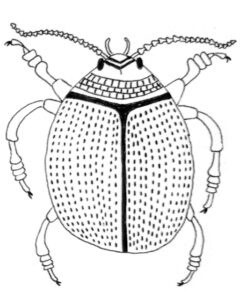

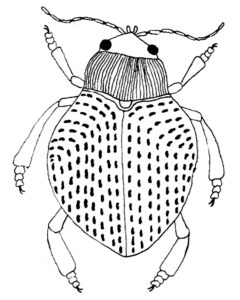

It was thanks to the teaspoon, you could say, that I found it. The beetle called me with its vibration. Leucrocota Sumptuosa or Magnificent of the sands. To reach it I walked at least fifty metres – I wonder how it is possible for a small insect to be heard at such a distance. She did not show any fear at all, picked up her wings and, perhaps, gave me a look of interest. I drew her details; shell, legs, antennae. I forgot the heat of the sun and the scorching sand. Then she spoke. And I, as I always do, listened to her.

Vibration is my people’s language Who doesn’t listen won’t know the power of the singing; Anguishes, surprises, terrors, hopes: Fluidity is in the secret, in the intimate power

Sibilla was searching for beetles; I try to find her and her story, and to do so I carve memories in silver.

The spoons’ handles are the antennae: there the beetles have sensilla, the sensitive receptors that allow them to perceive the world and orient themselves in it.

In their tiny vibration, I search for a language similar to deserts and forests, to emptiness and peace.

get updates and subscribe

for sales, exclusives, events and new creations